‘People thought that the conflict would be over in a few weeks, but it’s been already six years,’ an interview on World Humanitarian Day

Head of the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs in Ukraine, explains how the residents of eastern Ukraine are coping with the COVID-19.

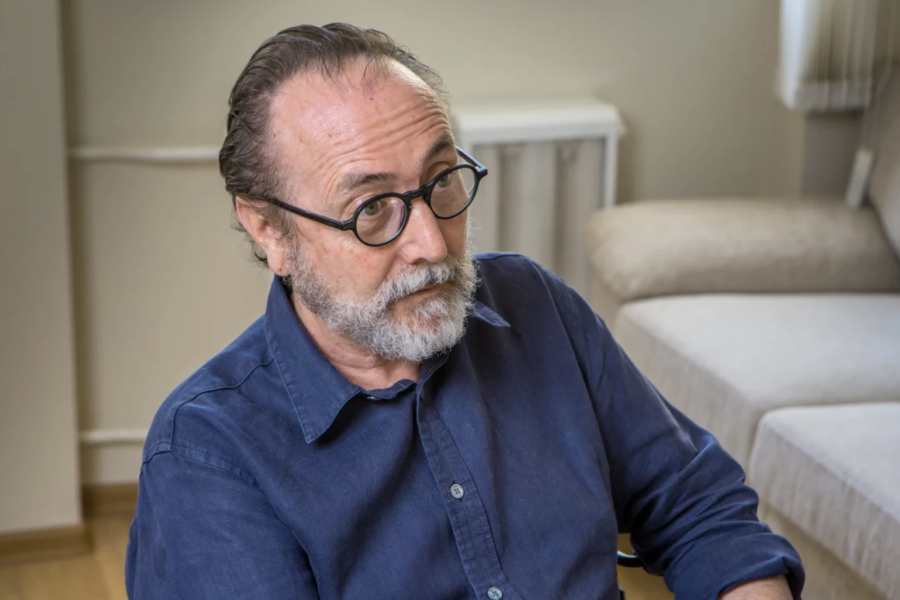

Ignacio Leon Garcia heads the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) in Ukraine. Ignacio has vast experience in humanitarian operations in different countries: he has worked for a number of humanitarian and development organizations in Brazil, Chile, and Equatorial Guinea, before heading OCHA Regional Offices in South Africa, Indonesia, Colombia, and also working as a regional coordinator in Angola.

Currently, Ignacio Leon Garcia and his colleagues from OCHA in Ukraine are coordinating the delivery of humanitarian aid to the people in the Ukrainian region of Donbas. OCHA coordinates the work of humanitarian organizations — UN agencies, international and national non-governmental organizations — which primarily focus their operations in the sectors of shelter and non-food items (NFIs); protection; education; health; water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH), and food security and livelihoods (FSL).

In an interview on World Humanitarian Day, commemorated globally on 19 August, Ignacio Leon Garcia tells NV about the most critical needs of Donbas residents whose homes are located on the ‘contact line’, and explains the challenges they have faced this year due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

The humanitarian response in eastern Ukraine is coordinated by six clusters: shelter and NFIs, protection, health, education, WASH, and FSL. In which of these areas do Donbas residents require support most?

Last year, we identified the needs of the population in eastern Ukraine. According to our estimates, 3.4 million people need humanitarian assistance. So, we are targeting 2.1 million of them. You can ask where this discrepancy in numbers comes from. It should be considered that some other organizations are also conducting relief activities.

Furthermore, we distinguish between needs in different sectors. Priority needs are those that could pose a threat to people’s life if they are left unmet, such as in the case with landmines remaining along the ‘contact line’. I was shocked to see the challenges these people face in their lives. Here, for example, there is a family residing close to the ‘contact line’: they make their living by cultivating their vegetable garden, and one day, their child went to play in the yard and was killed [by an explosive]. By a device that costs less than a dollar.

The second priority area for us is the restoration of civil infrastructure. People need such simple things as hot water, heating; they need to have windows repaired when the glass was shattered [due to the conflict]. If it is not done, then when winter comes, people will suffer from the cold.

Another important area of assistance is ensuring access to schools, hospitals, etc. We are talking about basic services that conflict-affected people must receive.

Furthermore, we should remember protection assistance. This includes both physical security and the possibility to move freely from one place to another, the possibility to access administrative services such as birth registration, and the possibility to exercise their rights.

Now, the challenges people in eastern Ukraine have already been facing are further compounded by the pandemic: as we know, at the end of February the first COVID-19 case was recorded.

So, for me, it is difficult to single out which needs are the most acute. People who reside along the ‘contact line’ have the same needs as you and me. When I wake up in the morning, I think about my breakfast, my family, my home, etc. That is, each of us has needs in different sectors. And we must be aware of this.

These people, they are the same as you and me; they feel the same pain as we do when we are hurt. Therefore, I do not want to focus on a particular sector but would rather talk about needs in different areas.

How was it before, in the beginning of the war? What was needed most then?

If we recall 2014, we’d see that at that moment, the lives of these people changed dramatically. They had immediate needs in various areas: an urgent need to access water, housing, food, and so on.

Based on my experience of work in different regions of the world, I can say that when people face conflicts such as the one in Donbas, they usually think that the situation will be over in a few weeks. Then one week passes by; two, three weeks, a month, two, a year …

And today, over six years have passed since the beginning of this conflict in Donbas, and many people who are still living there had initially thought it

would be over in a few weeks. In six years, no solutions have been found on how to meet the basic needs of local residents. For them, this is an additional psychological distress, as they are in the need of sustainable solutions to their problems, they want to know how to live in the future. Hence, six years later, we need more long-term solutions for these people, for their loved ones.

That's why in early 2020, we estimated that we would need about US$158 million to meet the basic needs of the people and to provide longer-term solutions. But due to the pandemic, the number of people with urgent needs has grown rapidly. Therefore, we asked our donors for an additional $47 million to address COVID-19 and its socio-economic consequences in eastern Ukraine. So far, we have received about a quarter of our appeal — some $56 million.

So, to sum it up, the needs of these people remain the same as at the beginning of the conflict, but today the people are more vulnerable.

We should put ourselves in their shoes. Imagine that some terrible things happen in your life. Then, you wake up the next morning, and they are still with you. And the next morning, and the morning after, and thus for all six years.

How many humanitarian organizations/missions are working in Donbas? Which ones?

When I said that we had appealed for a total of $205 million to provide humanitarian assistance to people in Donbas, by the word "we" I didn’t mean only our mission but all those who operate in the region.

As of today, 23 national non-governmental organizations (NGOs), 24 international non-governmental organizations, and nine UN agencies are working close to the ‘contact line’ in Donbas, for whom we’ve requested the funding.

Moreover, I am convinced that in this context, the most important mission is performed by NGOs who are the front-line responders. That is why we will support the capacity building of our national NGO partners. I am convinced that this is a general trend — to increase support for local organizations — not only in Ukraine but globally.

In Ukraine, there is a well-coordinated team providing humanitarian aid. The humanitarian community in Ukraine is very strong. Representatives of such organizations who work on the front lines risk their lives to help people. They are the ‘hands’, ‘eyes’ and ‘ears’ of the people they help. And very often they are also the ‘voice’ of all these people who are not heard.

What do you think about humanitarian convoys sent by Russia to the occupied territories of Donbas? Is it really necessary? Do these convoys arrive nowadays? What do they carry?

As a humanitarian mission, we receive notifications about Russian convoys. Sometimes we hear from locals when we visit schools or hospitals that certain things were delivered by a humanitarian convoy of the Russian Federation.

But we, as the UN, do not have the authority to check the contents of such convoys, evaluate them, to supervise how the assistance is distributed etc. We do not play any role in the inspection of those cargoes or in the distribution of aid.

How did the residents of Donbas get through the start of the pandemic?

The coronavirus came as a big surprise to all of us, both to those living in peaceful areas and to the residents of the settlements along the ‘contact line’. If, for example, someone had told me earlier that I would be self-quarantined at home with my wife, children, and a dog, I would not have believed it. No one was ready for that.

If we assess the impact of the pandemic in general, it all depends on the conditions in which the regions were pre-COVID, whether there were normal hospitals and qualified doctors. If you look at Donbas, even before COVID-19, this region was not in the best condition.

For example, for many locals, even a smartphone with Internet access is a luxury. There are additional difficulties: during quarantine, not all children had access to remote learning; not all adults could do shopping online when most stores were closed. For instance, such options were simply not available for the elderly, who were also left without access to their pensions.

According to a recent study by the International Organization for Migration, about 81 per cent of small and medium enterprises in eastern Ukraine have been greatly affected by quarantine restrictions: people have lost their jobs, which has had a significant impact on the economies of these regions. Furthermore, the virus does not distinguish whether these territories are controlled by the Government of Ukraine or not.

Coronavirus is more dangerous for vulnerable groups: the elderly, people with disabilities, and others. These vulnerabilities are overlapping; add a pandemic and a conflict on top of it, and all this makes them even more vulnerable.

Currently, the east of Ukraine is in the ‘green zone’ in terms of the number of coronavirus patients, i.e. the safe zone. But that doesn't mean they're less susceptible to it, no. The pandemic in the region has affected vulnerable ones the most. And these people [residing in Donetska and Luhanska oblasts] are very vulnerable.

When the pandemic started, Ukrainian funds and charity organizations such as the Return Alive Foundation were raising money to ensure that the Ukrainian Army has COVID-19 tests and PPE. Who has been helping the civilians?

To begin with, it should be noted that even the most developed countries in the world cannot test the entire population for coronavirus infection. That is, there are not enough tests anywhere.

In eastern Ukraine, we, together with the World Health Organization, aided local populations on both sides of the ‘contact line’, providing them with everything they needed. Not only with test kits, but also masks, sanitizers, personal protective equipment for health workers, and many more. Total worth of it is about $32 million.

You have already mentioned that for many residents of settlements on the ‘contact line’, gadgets and free internet access are a luxury. A new school year will begin soon. Are children in these regions provided with the necessary educational materials and technical means for remote learning, if required?

According to my information, as of 1 September, children will go to school, and the school year should begin according to the plan, not remotely, but in person, both in the Government-controlled and non-Government controlled areas. Of course, all participants of the learning process must comply with the necessary safety measures, sanitary and hygienic requirements, etc.

However, if there is still a need to organize remote learning, we are ready to allocate funds and provide support. Yet, the best solution would be to resume classes in normal mode — children should go to school. I understand how difficult it was both for parents and children to stay together at home for several months. This is also an important issue in terms of establishing and maintaining social ties among children, and their socialization.

How has the mood of people in Donbas changed since 2014? What are people hoping for? What future for Donbas are they envisaging?

I have experience in a lot of contexts: I have seen with my own eyes how people in Africa, the Balkans, Indonesia, Haiti, Colombia, Angola are going through different crises… And I can say that all these people want, regardless of in which country they live, is the right to a normal life. They want to be able to go to the hospital when necessary, send their children to school, withdraw their — not very large — pensions without having to travel hundreds of kilometres…

People in eastern Ukraine are desperate. They are exhausted, and they also want their normal lives. You know there is a point when it seems ‘that’s it, I can't cope anymore.’ And all of us — I, as a UN representative, and you, as a journalist, all have a common goal — to convey the voices of these people to others. Make them heard. Help them survive this crisis, give them the same future as you and I hope for.