Arbitrary Detention: The lost men of Dymer

//

UN Human Rights Monitoring Mission monitors met with two women, residents of Dymer in the Kyiv region, whose civilian relatives were taken by Russian soldiers when they occupied the area in late February last year. The men are still being held.

“The Russians interrogated our boys here. This is where they ate and this is where they went to the bathroom, everything happened here,” said Anna Mushtakova, standing in the boiler room of the local foundry in Dymer, a small town 46 kilometers north of the Ukrainian capital, Kyiv.

“Some witnesses confirmed that they shot at the ceiling to intimidate our boys,” said Mushtakova pointing at the pock marked wall of the foundry’s boiler room crammed with equipment.

Mushtakova, in her late fifties, said she had not seen her husband Ivan since day two of the invasion. The arrests began one day after the Russians occupied Dymer.

“They marched in on 25 February and they began arresting people the next day,” she recalled.

She said she last saw Ivan before he left the rural estate where they both worked and lived at the time to pick up his brother in a nearby village.

“Don’t go anywhere, it’s war,” she remembered telling him, but he went ahead anyway. She knew something was wrong when they did not come back.

She said she went to Dymer every two or three days desperate to find what happened to her husband.

“They strip searched me at the checkpoint, what were they looking for?” she asked. “I went around, I asked neighbors, I stuck a note on their doors but no avail. The neighbors did not see anything,” she said.

Mushtakova remembers that in early April, on the day the Ukrainian troops liberated the area, everyone rushed to the foundry that the Russians turned into a makeshift prison to search for clues about what had happened to their loved ones.

During a recent meeting with UN Human Rights Monitoring Mission in Ukraine (HRMMU) in June, Mushtakova and two other local women said they later found some documents and ID papers belonging to their men in the foundry’s safe that the Russian left intact when they fled advancing Ukrainian troops.

HRMMU monitors and publicly reports on the human rights situation in the country with the aim of strengthening human rights protection, fostering access to justice, and ensuring that perpetrators of human rights violations are held to account. HRMMU meets with victims and witnesses of human rights violations to hear firsthand their accounts and document any violations. This work ensures that the human cost of the war in Ukraine is documented and preserved and this will assist in ensuring accountability. HRMMU was deployed in March 2014.

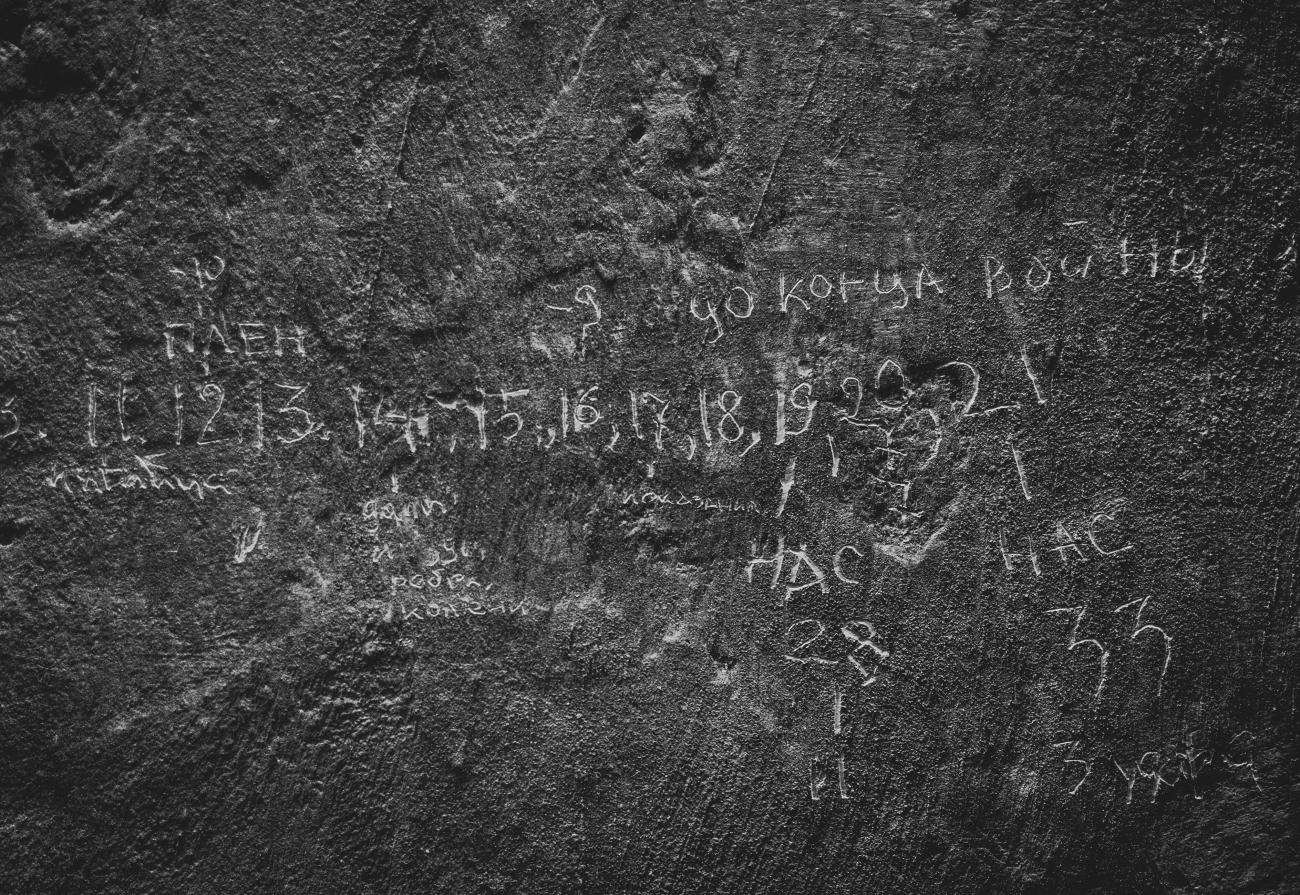

The women said they looked for clues in the scribbles scratched out in the stained brownish grey concrete wall of the makeshift detention room. As UN monitors visited 15 months later, the graffiti with the dates, the departures and the new arrivals were still visible.

“Ten were escorted out, we are now 28,” said one line carved into the wall with what might have been a sharp stone.

Dymer resident Olga Manukhina, 43, a mother of three whose husband and son had been taken by the Russians more than 15 months ago, said she recognized her husband’s writing on the wall.

“There was also an inscription in the corner at the bottom written by my husband to show that they had been there. Surnames, where they lived, phone numbers, in case someone saw it and could let me know that they were here, that they were alive,” she said.

According to UN reports, Russian forces detained large numbers of civilians within days of occupying parts of eastern Ukraine, as well as areas north of Kyiv. In a report released in June by HRMMU said it conducted 1,136 interviews with victims, witnesses and others. It said it documented over 900 cases of arbitrary detention of civilians, including children, and elderly people during the first 15 months following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

The report said most of these cases were perpetrated by the Russian Federation and detainees were frequently subjected to torture and ill-treatment. Some were summarily executed.

Local residents said 44 men of different ages and from various walks of life had been taken by the Russian armed forces from Dymer alone, a town of 5,500 inhabitants.

For Mushtakova the first real clue came from social media from a man who had been detained with her husband.

“He told me personally everything, how my husband suffered,” she said.

Mushtakova said this was how she learned that Ivan was detained at a Russian checkpoint.

“He was thrown to the ground without any explanation, beaten and put into a hangar for seven days. Then he was transferred to another hangar for another seven days. After that, he was transferred out,” she said.

Manukhina said her 20-year-old son Danylo used to be a worker at the very same foundry that would later become his prison.

“They simply took him from home, just came and took my husband and son,” she said, clutching a photograph of her missing men. “They didn't like something they found on his phone, a text message. There were seven of them. Six stayed outside with my son, and another one went inside with my husband. He looked around the house, checked all the phones, while those standing outside made my child take his clothes off, raise his clothes up because he had tattoos. She yelled to them to let them go."

“We are taking both the father and the son for interrogation," the Russian soldier announced.

“That’s it,” were the last words Maksym uttered as he kissed her goodbye, his hands already tied behind his back.

Never giving up

After more than 15 months of an agonizing wait, the Dymer women still don’t know where their loved ones are being held and how they are being treated but they heard that the men were taken to Belarus and then on to different prisons in Russia.

The women said they only knew that the men had been given a change of clothes because they came across photographs of them dressed in military uniforms. They said they reported the men’s disappearance to the Ukrainian authorities as soon as the Ukrainian forces regained control of the area. They were asked to be patient.

Most of the Dymer women received letters from their loved ones through Ukraine’s National Information Bureau but the letters said little about how their loved ones really were let alone where. Manukhina said the only letter she received from her husband just gave her a simple description of his schedule and living conditions.

She wrote back six times without any reply from him.

“There is no return address, they don’t say,” she remarked.

A high-ranking Ukrainian government official came to town recently, recalled one of the Dymer women. She asked them how they were doing. She took her by her hand and she told her things were bad and that her civilian son was in captivity.

“We will bring everyone home, but it will take time,” she said.